Music Brings Together Family Living with LCA6 RPGRIP1

Jessi Crawford fancied the clarinet when she played in her middle school band, while classmate Ted Beaman favored the trombone and guitar. Never did they dream their love of music would manifest a half lifetime later with the birth of their youngest son.

Atlas mixing it up!

Music is everything to almost 2-year-old Atlas – he loves to sing, he loves to dance, and he loves all kinds of music.

Before the toddler developed his interest in music, his parents noticed something about his eye movements.

“Out of nowhere,” at one-and-a-half-months old, his mom said, he developed horizontal and vertical nystagmus, characterized by side-to-side and up-and-down rapid, repetitive, uncontrolled eye movements.

Atlas and mom, Jessi

Atlas received his first pair of glasses at 3 months from Kellogg Eye Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan, about an hour drive from the family’s home in Toledo, Ohio.

A month later, doctors suspected Atlas had Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a rare genetic eye disorder in which the rods and the cones of the retina – the light-gathering cells – do not function properly.

Geneticists confirmed his genetic diagnosis as LCA6 caused by a mutation in his RPGRIP1 gene. LCA6 can be particularly devastating because of its rapid onset and progression.

“This took us completely by surprise,” Jessi said. “What do you mean, we both have this dysfunctional gene? What are you talking about?”

She was more than floored, especially because her oldest son, 11-year-old Brayden-Lee, has a rare, life-threatening form of autism and epilepsy. Brayden-Lee and Atlas also have a 7-year-old brother named Ronan.

Jessi found comfort and encouragement from the geneticist and the genetic counselor, but it took time to process the idea that her son’s vision would deteriorate.

“You have all these stigmas around losing your vision being the worst thing on the planet, but I realized he could still have a happy life. He’s not dying, he’s just going to lose his vision – that perspective helped a lot.”

She’d already enlisted state and local resources to help Brayden-Lee, so she began searching for any available support and assistance for Atlas.

“I found him an O&M (Orientation and Mobility) specialist, a developmental specialist, and a vision specialist, so he wouldn’t fall behind in anything – movement, sensory output, anything.

“I was still really kind of sad and overwhelmed, and, of course, worried, because I never experienced anything like this before. My oldest son had occupational therapy, speech therapy, hospital visits galore, but I never dealt with anyone who couldn’t see.”

LCA6 RPGRIP1 preclinical research underway

Atlas turns 2 in May and he’s quite advanced, talking in 4-, 5-, 6-word sentences.

“He knows his shapes and he’s working on colors, which is hard because he sometimes blends colors.”

Atlas has no vision from the midline of his eye, down. He has vision above, for now, and cannot see close up.

Jessi and Ted’s little boy underwent eye muscle surgery in February to release his eyes from crossing, which has helped his vision.

Jessi connected with Odylia Therapeutics, a biotech working on late-stage preclinical studies for a potential treatment for the RPGRIP1 mutation, and, hoping to help advance research, she authorized the company’s use of images taken of her son’s eyes during the surgery.

The Atlanta-based business is developing an investigational gene therapy to treat vision loss caused by LCA6 and is working with vector technology developed by Odylia Co-Founder Luk Vandenberghe, PhD. The research builds on data generated at Massachusetts Eye and Ear in the labs of Vandenberghe and Eric Pierce, MD, PhD, a physician and surgeon at Mass Eye.

The company is preparing its IND submission, or Investigational New Drug Application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). An IND is a request from a study sponsor to obtain FDA permission to start human clinical trials.

Odylia hopes to begin trials in 2025 and is seeking partnership or philanthropic funding for the estimated $3.5 million development costs.

Jessi said she’d like to enroll Atlas in a clinical trial, just not the first one because she fears possible, yet undiscovered, side effects from experimental treatment.

Watching Mickey Mouse and Listening to Rock ‘n’ roll, Country, Celtic, and Native American

Atlas loves music, singing, and watching TV.

“He loves watching Mickey Mouse-anything. He stood at the mirror, pointed at his shirt in the mirror and said, “Mickey Mouse, blue shirt, mamma.”

A happy child who loves raisins and pizza, he reaches for things and gets his spoon or fork to his mouth, while getting food into it is another thing.

Jessi said Atlas has a tough time with the letter ‘f’ and says shork when he means fork.

“He tells me every day, fork and bowl, fork and bowl, or ‘shork a bow, mamma, shork a bow.’” Jessi said just thinking about it makes her laugh.

The 31-year-old characterized herself and her fiancée, 32-year-old Ted, as “both huge, huge, musical people,” beginning back in the school band, when they started dating in their teens and later went their separate ways, only to start dating again four years ago.

“The fact that Atlas likes music so much is better for us. He loves Disney music, also rock, country music and Celtic, and Native American.

“So, when I say we’re well rounded, we’re well rounded.”

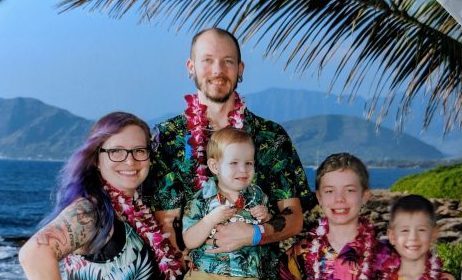

Jessi, Ted, Atlas, Brayden-Lee, and Ronan