Genetic Tests Glean New Diagnoses for People Living with Rare Inherited Retinal Disease

Three people who received diagnoses of Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) in recent years – but lived most of their lives thinking they had retinitis pigmentosa (RP) – gave us the opportunity to hear their stories at a special session of the VISIONS 2022 conference this summer.

An RP diagnosis is currently given to patients with photoreceptor degeneration but good central vision within the first decade of life; an LCA diagnosis is given to patients who are born blind or who lose vision within a few months after birth.

In the middle of a two-day conference hosted by the Foundation Fighting Blindness, several of us from Hope in Focus in an LCA Mix & Mingle session heard about the sometimes-rocky road to getting a confirmed genetic diagnosis of a rare inherited retinal disease (IRD), especially in the years before access to genetic testing.

Ultimately, though, that difficulty did not hold back these individuals from creating happy and productive lives because they did not allow their blindness to define them.

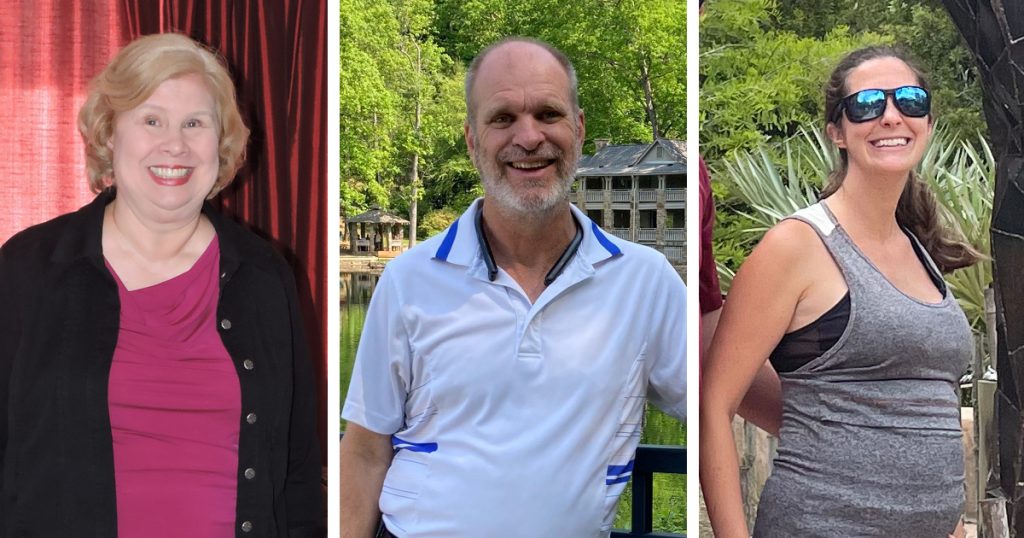

Linda Joy Wirth, Russ Davis, and Emily Townsend Cobb

Linda Joy Wirth

Blind since birth, Linda Joy Wirth, now 75 and living in Lakewood, Colo., was diagnosed with RP in the 1960s. Because she was told from an early age that nothing could be done for her blindness, she stopped thinking about her diagnosis and focused on her education, marriage, and children.

Then she thought: “You can never cure something if you can’t diagnose it.”

In the 1990s, she sought out a highly recommended doctor who treated her with a strong dose of cruel words.

“ ‘You’re blind. What do you want me to tell you?’ ” she recalled the doctor saying. “I was so distraught by the visit; I did not go back to the doctor for years and years and years.”

About 10 years ago, though, she went to a Foundation conference, where she received a referral to a Denver retinal specialist by the name of Dr. Alan Kimura, who changed her life.

“When I finally saw Dr. Kimura, I said I don’t even know why I’m here. I walked out two hours later, and I was walking on cloud nine. It’s so important to have the right retinal doctor.”

Dr. Kimura told her she had LCA. Genetic testing gave her a confirmed genetic diagnosis of LCA10, caused by mutations in the CEP290 gene.

Linda encourages people to get genetically tested to pinpoint the diagnosis, and then, like her, to be aware of the possibility of participating in a clinical trial to advance research into treatments and cures.

People told Linda along the way that because of her blindness, she shouldn’t marry or have children or follow her passion for acting. And, of course, she heard those stinging words from that earlier doctor: “ ‘You’re blind. There’s nothing we can do.’ ”

Linda is a retired clinical social worker in geriatric long-term care, an actor in a theater company, a Foundation volunteer, a mother of four, a grandmother of seven, a motivational speaker, and the author of “Just Because I Am Blind Does Not Mean I Can’t See!”

Russ Davis

Russ Davis, 60, of Jacksonville, Fla., still gets confusing information about the cause of his rare inherited retinal disease.

“One minute I hear it’s probably LCA, or no, that it’s classic RP. I got that at the conference.”

Some retinal experts do consider LCA to be a severe form of RP.

In 2019, Russ received a genetic diagnosis of LCA2, caused by a mutation in the RPE65 gene. Dr. Stephen Russell at the University of Iowa told Russ he could have RP or LCA.

“ ‘It could be either one,’ ” he recalled the doctor saying. “ ‘But at your age with so few retinal cells, we’re not going to know.’ ”

Russ said he’s a little frustrated with the lack of a certain label for the disease, but it’s not going to change his life.

“The blindness part, that’s fine. I am who I am. It doesn’t control my life. But I’d like to have answers.”

These days, Russ is going with LCA.

His vision loss occurred at birth. Growing up he could read a book with a bright light, ride a bike, and he enjoyed long-distance running.

“I could see most everything, except at night when everything disappeared. When the sun went down, I was toast,” he said. “There was nothing there. There was darkness and light bulbs.”

His vision worsened early in his career in his mid-20s working for the State of Florida, looking for people who owed child support and wanted to stay missing. The job was fun for 30 years but about 10 years ago, with his vision getting worse and work getting harder, he retired.

Russ and his partner, Denise Valkema, were like a comedy team at the LCA session, riffing off each other’s words and making the Mix & Mingle group erupt in rounds of laughter.

Denise, who lives with optic nerve hypoplasia, which is an underdevelopment of the optic nerve, met Russ through the National Federation of the Blind. Denise served as NFB’s Florida Affiliate President for seven years.

They both serve on the organization’s board. Their priorities include working with Congress on myriad pieces of legislation to bring about better accessibility to medical care, computer technology, banking, voting, and more.

“The blind community is still not able to participate fully in society because we don’t have access to all the aspects of living that the sighted community has,” Russ said. “Try finding a talking blood pressure cuff.”

Russ advocates for people with diminishing eyesight, reassuring them that that life will go on.

“It’s all about your attitude. I try to tell them, no, that it’s not going to be easy. Lots of times, it’s going to be difficult. There are a lot of things to adjust to. You simply find new ways to do the things you were doing before.

“You can’t let your loss of eyesight define who you are or control you. You have to own it and not let it control you.”

And he lives his words.

“There’s so many times in life, you have the option to laugh or to cry, and I’m going to pick laughter. It would be very easy to pick the other one.”

Emily Townsend Cobb

With a 2½-year-old daughter, another one on the way, and a pediatric physical therapy career, we were lucky we had the chance to talk with Emily Townsend Cobb at the LCA session.

Doctors diagnosed Emily with RP at age 3. Now, 33, she received a confirmed genetic diagnosis in 2019 of LCA13, caused by a mutation in the RDH12 gene.

Emily is in that age group of people misdiagnosed for years before the advent of genetic testing.

“Thirty and over, that’s how it went,” she said.

Getting the confirmed diagnosis didn’t really change her life, especially because LCA13 research is in preliminary stages.

“Now I sit and wait for my number to be called,” Emily said, referring to the possibility of a treatment or cure for her form of LCA. “While we wait for all these things to happen, we have to live life.”

Emily’s husband, and her mom and dad accompanied her at the conference. Her father, Clay, introduced himself, saying, “Oh, I’m the proud father of two girls with RDH12 and I’d do anything to help them.”

As he broke into tears, his wife, Sue, leaned into him, saying, “He’s a crier.”

Without having to say much more, it became clear why Emily credits her family for their loving support and positive approach toward life.

She said she receives 150 percent support from her family.

“That support is so important for anybody, but especially if you have a disability.”

Doctors also diagnosed her 31-year-old sister, Ashley, with RP, and she later received a genetic diagnosis of LCA13 (RDH12).

Emily remembers reading newsprint as a pre-teen and playing soccer, but her vision profoundly worsened as a teen-ager, a tough time for any kid, but especially for her as she was losing her sight.

About the same time, she learned she had LCA but didn’t undergo genetic testing because genetic data was still being mapped out.

We talked with Emily after the session when she returned to her home in Jacksonville, Fla., where early on, she said, her mom set her up with a therapist who had RP, which helped build her confidence as a teen-ager.

She put off using a cane until college and in her sophomore year got her guide dog, a black lab named Fergie, now retired to pet life after 11 years of service.

“She’s currently snuggled up to me on the couch while I fold laundry,” Emily said as her little girl, Elora, napped.

Her second daughter is due in October. And, oh, did we mention she runs half-marathons and is a triathlete?

Emily takes part in triathlons with her husband, Ryan; they are tethered during the running and swimming races and ride a tandem bike for the cycling portion.

“If you ever want to test the strength of a marriage, blindfold one of you and tether to the other,” Emily quipped.

She and Ryan talked about the chances of their children being born with LCA. She recalled her husband saying, “ ‘Emily, if they’re going to end up as awesome as you, I want to.’ ”

They knew their children could be born with LCA, but they also knew the rarity of the disease. Emily said the chances of having a child with LCA are about one in 400.

“I’ll take those odds,” she said. “I’m pretty happy that I’m here.”