Three-year-old Luca Corso’s preschool teacher announced that everyone should quickly sit on their floor shapes for carpet time. As the other children eagerly scattered to their assigned spots, Luca wandered. He wasn’t being disruptive—he just wasn’t sure what to do. Even with glasses and a cane, he couldn’t locate a flat shape on the floor. Luca’s vigilant parents, Blair and John Corso, along with his early intervention team, got involved, and the preschool quickly provided him with a small chair for carpet time.

Diagnosis Shock

Luca was diagnosed with the recessive AIPL1 gene mutation that causes Leber congenital amaurosis 4 (LCA4) when he was about 14 months old. According to the Foundation Fighting Blindness, this rare but severe form of LCA affects “only a few hundred people in the US and less than 10,000 people globally.” The news was devastating to first-time parents, Blair and John, and almost unbearable when they were told that their little boy would likely lose all of his vision by age four.

A Ray of Hope

The family was given a ray of hope after hearing about a new LCA4 treatment developed by MeiraGTx that showed efficacy in a trial involving 11 children in the United Kingdom (UK). The therapy, which uses a human-engineered adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver copies of the therapeutic gene into remaining photoreceptors, has not yet been approved for use in the UK or the United States. If successful, the treatment could restore some of Luca’s vision.

Hoping beyond hope that the treatment becomes available before Luca turns four, the Corsos know that his window of opportunity is rapidly closing. Another potential hurdle is the cost. “Not only does the treatment require approval, but we don’t know the cost, since the trial would no longer fund it,” Blair said.

Balancing Emotions

For Blair, the news of the UK trial’s success was at once wonderful and disheartening. “I saw one of the boys who had the treatment and spoke with his mother,” she said, choking back tears. “After the treatment, he could see facial expressions. It would mean everything if Luca could experience that too. When I read stories about the children treated, it struck me that being able to see things like that could really help Luca interact with us and his peers.”

The Diagnostic Journey

When Luca was born, the Corsos were living with Blair’s parents while they searched for a house. It was then that they first suspected something was wrong with Luca’s vision. “My Dad kept wondering why Luca’s eyes were going back and forth so much,” Blair said. “Was it normal?”

The pediatrician was also concerned about their four-month-old son’s eye movements (nystagmus) and quickly referred Luca to a local eye doctor. After confirming Luca’s vision loss but seeming less worried about the nystagmus, the eye doctor referred the family to Mays Al El-Dairi, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist and neuro-ophthalmologist at Duke University Eye Center.

“Dr. El-Dairi examined Luca and mentioned the possibility of LCA and recommended genetic testing with Ramiro Maldonado, MD, a retinal specialist at Duke,” Blair said. Dr. Maldonado arranged the genetic testing and wanted to do an electroretinography (ERG), a diagnostic test that measures the electrical activity of the retina. But Luca needed to be at least a year old to have the ERG.

Test Results

“Luca was about 14 months old when the ERG was done, and it showed that he had about 50 percent of his vision. The genetic test indicated LCA4, and Dr. Maldonado said that our toddler would likely be blind by age four,” said Blair. “It was a very rough day. John was at home sick, our dog had just died, and my mother and I were in the surgery waiting area, bawling our eyes out.” Luca was Dr. Maldonado’s first case of LCA4.

Help!

Like all parents hearing an LCA diagnosis, the Corso family was desperate for more information and support. They immediately began looking on Facebook, where they discovered Hope in Focus (HIF). Through HIF, they started connecting with the LCA community, and Blair was paired with an HIF Ambassador, Ashlyn, whose young son has LCA10.

“I can pick up the phone or shoot a Facebook message to her, and I don’t have to explain things,” Blair said. “It’s wonderful to have the support, especially when you don’t know what you are doing. If I have a question, Ashlyn offers input or helps me reach out to someone else. It’s like a big family of support, and it’s so encouraging to know that other children with LCA are thriving.”

Early Intervention

Early in Luca’s diagnostic journey, the local eye doctor suggested pursuing ‘early intervention’ due to his vision loss. Unsure what ‘early intervention’ meant, the Corsos learned more about it and reached out for help, a decision that would prove crucial in Luca’s journey.

The Corso’s live in North Carolina, where early intervention is available through the state’s Children’s Developmental Services Agencies (CDSAs). “They sent some people out to talk with us about LCA, and there was an actual team involved. We had a caseworker, a vision teacher, and an orientation and mobility coach,” Blair said. “They were fantastic in guiding us about how to teach Luca and helping him keep on track with his learning.”

Blair stressed the importance of accessing early intervention and said, “Our CDSA team visited us before Luca was in preschool and worked with him at least once a week. When he began preschool, the team went there as well, helping the teacher to understand his needs, such as where to position him so he could see in the classroom.”

The team also conducted many in-home learning sessions. “They suggested different things to support Luca in school and at home. His occupational therapist recommended that we help him learn how to move to songs so he wouldn’t stand motionless while his classmates danced,” Blair said. “You know, it’s not always obvious or intuitive for parents to know what to do!”

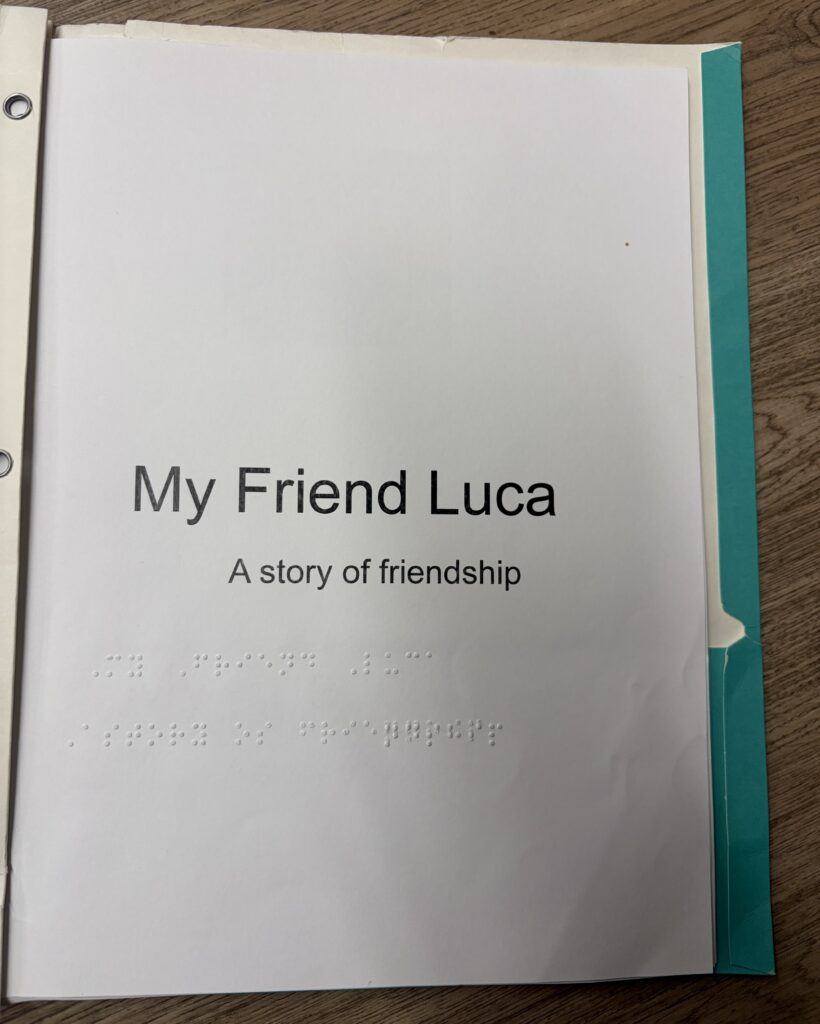

One of his vision teachers, Ms. Charli, created a book for his preschool called “My Friend Luca,” which explains that Luca’s eyes don’t work well and that he uses his hands to see the world. “It helps other children understand why Luca might want to hold their hand or reach out and touch their face,” Blair said.

There were also monthly trips into the community with his orientation and mobility coach, Ms. Annette. “We went to the strawberry patch, the grocery store, and Lowe’s,” Blair said. “We did normal things so she could observe him in public—such as how he navigated with his cane.”

Luca’s current mobility and orientation coach, Mr. Mike, is the past president of the Maryland School for the Blind and a member of the local school system that now serves Luca’s needs. “Mr. Mike is just amazing!” said Blair. “He focuses on learning through play and wants Luca to think of him as a fun grandpa. He even got Luca to sit on the swing, which he was terrified to do.”

Going Forward

The Corso’s attended this year’s Hope in Focus Family Conference for the first time and found the information and variety of speakers very helpful. Meeting other families with children who have LCA was supportive, especially those dealing with the same gene mutation and its consequences.

Blair and John recommend that parents seek early intervention resources for their child with LCA and be open to help. They hold out hope that the treatment in the UK might become available for Luca while continuing to prepare him for a future where he is blind.

For now, the couple finds great joy in their little boy and his “can-do” spirit, delightful personality, and bright, engaging mind. They have and will continue to ardently advocate for Luca as he walks into the future surrounded by their unending love and support.

Information on the treatment for LCA4: https://www.fightingblindness.org/news/lca4-gene-therapy-restores-meaningful-vision-for-blind-children-1861